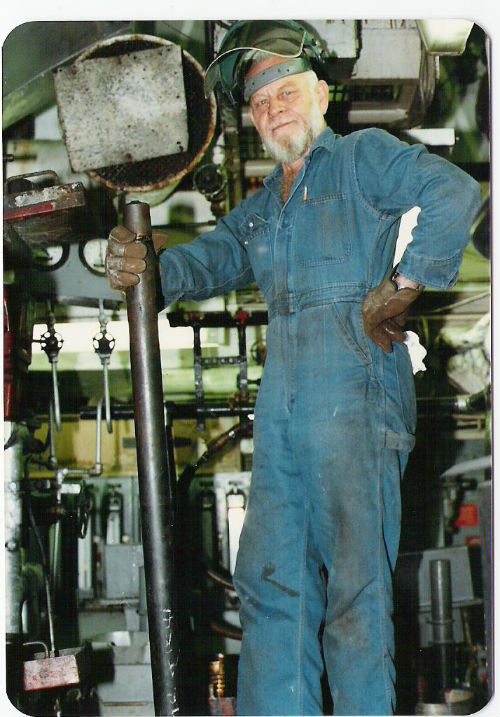

While I was in Memphis last week I got to spend some time with my dad’s brother, Bud. He was wearing an 8th Air Force ball cap so I asked him to tell us about his service. From his enthusiastic telling of “war stories” it seemed clear that the time he spent on those B-17s were among the best years of his life. He told me about training to be a pilot, eventually washing out, and then being sent to gunnery school. Which is how he wound up being the belly gunner on the B-17, which he called the best damn plane every built.

He got to England late in the war and flew 19 missions before the Germans capitulated. He said the guys in the early days had it a lot worse because they didn’t have the P-51 fighter escorts that he enjoyed. Even so, he remembered having one of those ME-252 fighter jets in his sights for a brief instant, but it was too fast to keep a bead on. He was glad that they never faced them in force.

Their biggest problem was flak and it was apparently pretty scary stuff. The got hit frequently (he said after one mission they counted over 100 holes of varying size in the fuselage). And once they took a direct hit over Germany, it killed the navigator and severely injured the co-pilot. They lost both starboard engines which made it difficult to control the planes and maintain altitude. They managed to make it as far as Belgium where they crash landed. Apparently the Germans had pulled out only days earlier and they made it back to London without being captured.

Anyway, the thing he told me which really struck me was this: They would normally fly a mission in 3 day rotations, sometimes more often depending on the targets, and less depending on weather. Duty rosters were posted on the lavatory door (I guess so everyone would see them eventually). And if your name appeared on the roster, you didn’t make any plans. I said why, so you could prepare? And he said “no, because everyone always assumed they wouldn’t be back.”

I can’t imagine the courage these guys had to have.

This is not Uncle Bud’s plane, unfortunately I don’t have a picture of his.