That’s my life. And upon reflection, it’s good. Not all good and not all the time, but better than I might have hoped for. Or perhaps deserved. So, what triggered my bout of self-analysis to reach these not so profound conclusions? I blame the internet. Here’s what happened:

A question was posed on Quora: “What is something you wish you had known sooner?” And this was the featured answer:

I’m 77. I created four successful businesses, married two beautiful women (one at a time) have two great sons, and retired at 49. My life has been full. And it really doesn’t matter – none of it. I wish I’d known that in the beginning – that it all wouldn’t matter. I beat myself up most of my life trying to accomplish success and I could have had a much easier time of it. I was chasing someone else’s dream, not mine. No 14 hour days, six days out of the week. No heart attacks. No ulcers. No enemies. I could have learned the piano, painted, sculpted, read more books, learned to dance the salsa, had more dogs. At the end of life, and mine is just around the corner, the important stuff is the stuff I didn’t have time for. I can’t speak for all wealthy people, but the ones I know are pretty damn empty. We come into the world naked and we leave pretty much the same way – and there are no “Mulligans”. If you don’t get it right the first time, too bad for you. I’m too old to climb the mountains I always wanted to climb, too old to buy a dog, too old to learn to surf, too old to learn the piano. All the good stuff is behind me. Don’t get stuck in a life that isn’t yours.

Damn. Well, I’m happy to report that I don’t feel that way about my life. I don’t know that I ever really had much of a plan–I just went with the flow and it led me to this here and now. At 65 I may still have a few adventures ahead of me but I don’t expect there will be any life-changing events in store. It is what it is and I’m content to ride it out to its natural conclusion. Granted, I’m in no hurry to get to the end of days but you never know what’s left. I’m certainly not going to waste time wishing for something else.

Okay, maybe that’s not entirely true. Sometimes when I am trying to ease myself into sleep mode I’ll engage in some fantasizing. No, not THAT kind, I can always pay to make those come true! I mean the fantasy of going back in time, knowing what I know now, and reliving my life accordingly. I usually imagine returning to various decision points in the past and deciding to do something different. For example, in my do-over life perhaps I’d enlist in the Army after high school. That’s something I never even considered at the time seeing as how I’d just managed to avoid being drafted. But who knows where that might have led me? One thing is for sure, in all these fantasies I end up rich beyond imagination–I’m buying all those IPO tech stocks like Microsoft, Google, and Apple!

So, while I’m in this mode of thinking about altering the past I happen upon an article in The New Yorker “What If You Could Do It All Over?”. Hmm, it seems my fantasy is actually quite popular!

“The thought that I might have become someone else is so bland that dwelling on it sometimes seems fatuous,” the literary scholar Andrew H. Miller writes, in “On Not Being Someone Else: Tales of Our Unled Lives” (Harvard). Still, phrased the right way, the thought has an insistent, uncanny magnetism. Miller’s book is, among other things, a compendium of expressions of wonder over what might have been. Miller quotes Clifford Geertz, who, in “The Interpretation of Cultures,” wrote that “one of the most significant facts about us may finally be that we all begin with the natural equipment to live a thousand kinds of life but end in the end having lived only one.” He cites the critic William Empson: “There is more in the child than any man has been able to keep.” We have unlived lives for all sorts of reasons: because we make choices; because society constrains us; because events force our hand; most of all, because we are singular individuals, becoming more so with time. “While growth realizes, it narrows,” Miller writes. “Plural possibilities simmer down.” This is painful, but it’s an odd kind of pain—hypothetical, paradoxical. Even as we regret who we haven’t become, we value who we are. We seem to find meaning in what’s never happened. Our self-portraits use a lot of negative space…We may imagine specific unlived lives for ourselves, as artists, or teachers, or tech bros; I have a lawyer friend whose alternate self owns a bar in Red Hook. Or we may just be drawn to possibility itself, as in the poem “The Road Not Taken”: when Robert Frost tells us that choosing one path over the other made “all the difference,” it doesn’t matter what the difference is. Carl Dennis’s poem “The God Who Loves You” tries to make that difference concrete. Dennis poses a question to his protagonist, a middle-aged real-estate agent: “What would have happened / Had you gone to your second choice for college”? A different roommate, a different spouse, a different job: could it all have added up to “a life thirty points above the life you’re living / On any scale of satisfaction”? Only “the god who loves you” knows for sure. It’s an unsettling thought; Dennis suggests that we pity that all-knowing god, “pacing his cloudy bedroom, harassed by alternatives / You’re spared by ignorance.”

Swept up in our real lives, we quickly forget about the unreal ones. Still, there will be moments when, for good or for ill, we feel confronted by our unrealized possibilities; they may even, through their persistence, shape us. Practitioners of mindfulness tell us that we should look away, returning our gaze to the actual, the here and now. But we might have the opposite impulse, as Miller does. He wants us to wander in the hall of mirrors—to let our imagined selves “linger longer and say more.” What can our unreal selves say about our real ones?

Their mere presence in our minds may reveal something about how we live: “Unled lives are a largely modern preoccupation,” Miller writes. It used to be that, for the most part, people lived the life their parents had, or the one that the fates decreed. Today, we try to chart our own courses. The difference is reflected in the stories we tell ourselves. In the Iliad, Achilles chooses between two clearly defined fates, designed by the gods and foretold in advance: he can either fight and die at Troy or live a long, boring life. (In the end, he chooses to fight.) But the world in which we live isn’t so neatly organized. Achilles didn’t have to wonder if he should have been pre-med or pre-law; we make such decisions knowing that they might shape our lives…

Sorry for the long excerpt, but I found the article quite fascinating. Give it a read if you are so inclined.

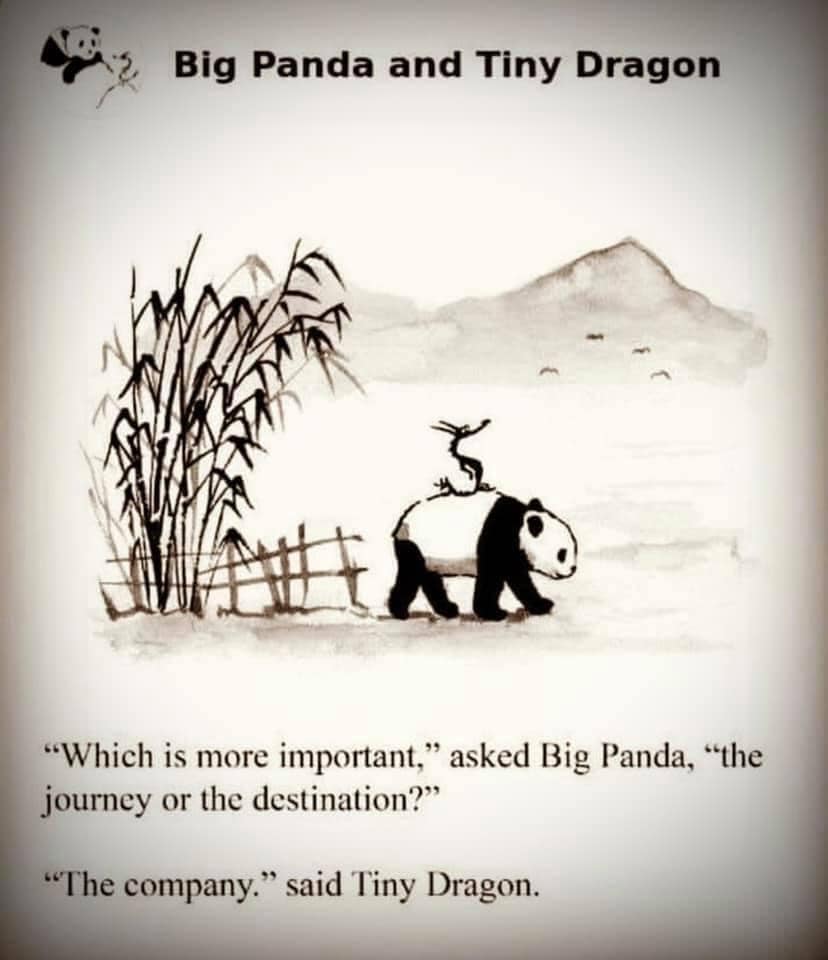

This got me thinking about those crossroads and decision points I’ve encountered in my own life. The big ones that changed everything like deciding NOT to give my firstborn up for adoption or leaving my Amerian life and making the move to Korea. And the subtle ones, like walking into a bar in Flagstaff, Arizona, that put me on the road to where I am today. Would I change those decisions knowing what I know now? How could I? It would mean losing all that makes me who and what I am. I’ve come up with a workaround in my fantasies to avoid that pitfall; I basically create an alternate universe and my “real” life in this one is unaffected by any changes I pursue in the new universe. Yeah, I have WAY too much time on my hands, don’t I?

So much for looking back, let’s move on to learning. Obviously, I’m an old dog so what new tricks are out there for me to learn? But once again, the internet is here to save the day. Thanks to Althouse I learned a little about Saint Peter Damian, someone I had heretofore never heard of:

“[H]e introduced a more-severe discipline, including the practice of flagellation… Another innovation was that of the daily siesta… Peter often condemned philosophy. He claimed that the first grammarian was the Devil, who taught Adam to decline deus in the plural. He argued that monks should not have to study philosophy, because Jesus did not choose philosophers as disciples, and so philosophy is not necessary for salvation.”

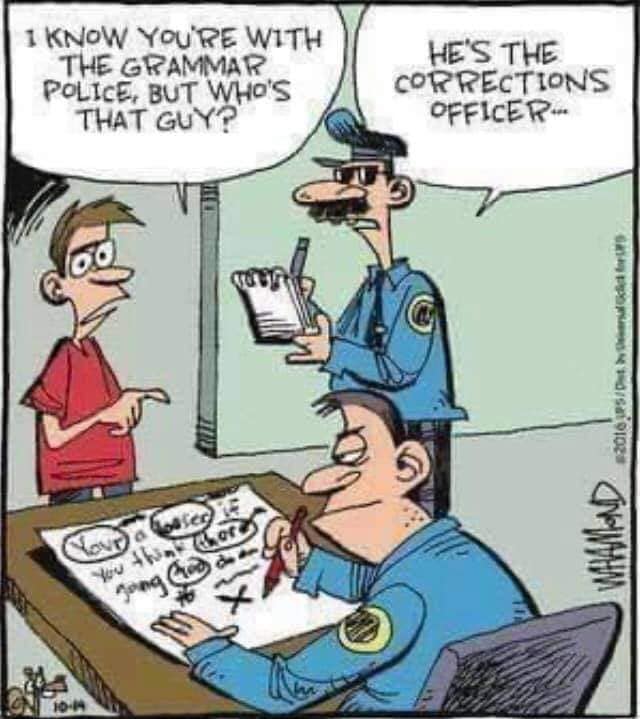

My big takeaway from the above was that Satan was the first grammarian. Which is why we say “the devil is in the details”, right Kevin Kim?

That’s enough learning for one day I think. So that leaves living.

Living a healthy life means taking appropriate steps to avoid viral diseases.

Speaking of COVID, where did that killer virus originate?

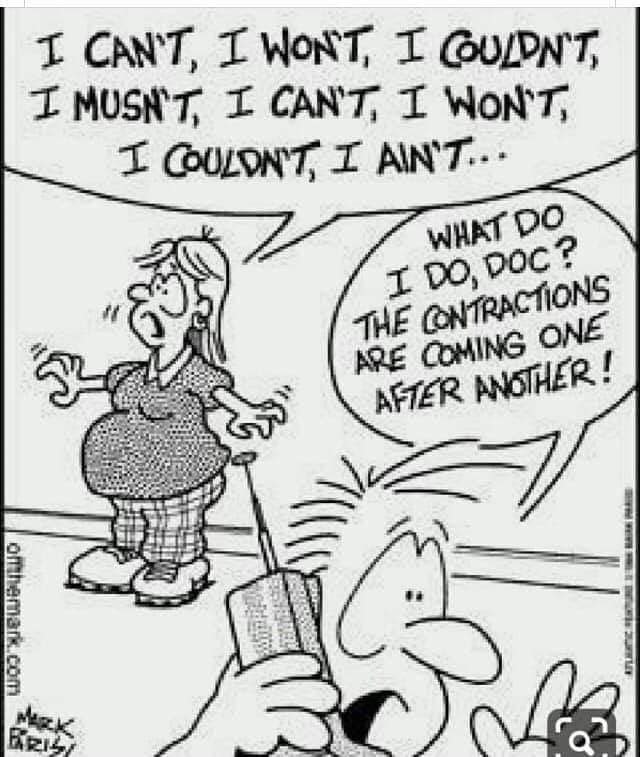

And despite the inevitable ups and downs that come with living, you’ve got to keep your sense of humor and have some laughs. Luckily, I’m a very punny guy!

So, there you have it. Living, learning, and looking back. A philosophy for a lifetime.

Alright, I’ve got that out of my system. We’ll get back to normal around here tomorrow with a report of yesterday’s crazy hike in the jungle. It was a path I should not have taken.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.I shall be telling this with a sigh

–Robert Frost

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Interesting meditation on the counterfactuals. Indeed, the longer you’re alive, the narrower your horizon of possibilities becomes. A wide, non-specific future ultimately narrows to one possible outcome. I think about that fact in terms of my own eventual demise: in the end, I’m going to die a certain way, from certain causes, in a certain place, and at a certain time. All of that is nebulous right now, but as time marches on, the future slowly resolves itself into clarity. It’s like the collapsing wave function with Schrödinger’s cat: at first, the cat is both alive and dead, but when you peek into the box, the cloud of possibilities suddenly crystallizes into one specific outcome. Enjoy the nebulousness of your future while you can! As for living without regrets, well… I think the best I can manage is to live with a minimum of regrets. My suspicion is that people who say “I regret nothing” are lying.

Yes, with age comes ever-increasing limitations on available choices. I’m definitely in the riding it out mode now. Still, the randomness of it all is thought-provoking, at least for me. In 2004 I was gung-ho on getting work with the military in Iraq, applying for lots of jobs. The only offer I got though was from Korea. Iraq would have been short term, maybe a year-long assignment. Korea changed my life. I thought marrying Jee Yeun was part of that destiny, but the fates had other ideas. And so here I am living the life I rejected when I chose marriage. Life for me at least has been a rudderless ship. Nothing but the illusion of control.